Of all of the socialist and communist despots in history, Mao Zedong is responsible for the greatest amount of human suffering and death.

Mao’s journey to prominence began with his leadership role in the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in the 1920s and 1930s, during which he led a guerrilla warfare campaign against the Nationalist forces, also known as the Kuomintang. His ascent was facilitated by a potent blend of his ability to mobilize peasantry, strategic acumen, and his ideological commitment to Marxism-Leninism.

Following Japan’s surrender at the end of World War II, civil war resumed between the CCP and Nationalists, resulting in the former’s victory in 1949, and the evacuation of the Kuomintang to the island of Formosa, now known as Taiwan. This led to the establishment of the People’s Republic of China, with Mao as its preeminent leader.

Early Years and Purges

Mao introduced several early socialist policies intended to transform China into a modern, self-reliant nation. The Land Reform Law of 1950 sought to redistribute wealth by seizing land from the gentry and redistributing it to poor peasants. This policy significantly reduced the wealth and influence of the traditional landlord class while increasing the CCP’s support base.

In 1953, Mao ordered the first of many Five-Year plans, focused on rapid industrialization. Modeled after Soviet-style command economies, it emphasized the growth of heavy industry at the expense of consumer goods. The Plan also entailed the collectivization of agriculture, which led to the formation of agricultural cooperatives and collectives. Despite numerous challenges, the Plan was declared a success, achieving significant industrial and infrastructural growth.

However, Mao’s policies were accompanied by harsh repression and purges, particularly during the Anti-Rightist Campaign of 1957-59. This began ostensibly as a liberalizing initiative, the Hundred Flowers Campaign, which encouraged intellectuals to criticize the government and its policies. When criticisms became intense, Mao reversed course and launched the Anti-Rightist Campaign. This saw a severe crackdown on intellectuals and party members accused of bourgeois tendencies, with an estimated 550,000 people executed.

The purges effectively silenced public dissent, creating an atmosphere of fear and uncertainty. Those accused often faced public humiliation, imprisonment, or execution. Many were sent to labor camps, where conditions were extremely harsh. The purges served not only to eliminate opposition but also to consolidate Mao’s position within the party and the nation, reinforcing the idea that deviation from the party line could have severe consequences.

The purges of the 1950s and the climate of repression set the stage for one of the most devastating periods in China’s history, the Great Leap Forward. Driven by Mao’s vision of a rapid transition to communism, this policy led to economic desolation and a catastrophic famine that claimed millions of lives.

Great Leap Forward

Mao Zedong’s “Great Leap Forward,” launched in 1958, sought to rapidly transform China from an agrarian economy into a modern, industrial socialist society. The plan relied upon coerced industrialization and collectivization, aiming to make China a global superpower on par with the United States and the Soviet Union.

In the realm of agriculture, the Great Leap Forward’s policies led to the creation of large-scale communal farming units known as People’s Communes. Approximately 750,000 agricultural cooperatives were merged into about 23,500 communes, each comprising approximately 5,000 households. Peasants were to work together, sharing tools, draft animals, and harvests, and they were promised access to modern amenities like public dining halls, free health care, and education. Many traditional familial structures and small-scale farming activities were disrupted or even abolished as part of the reorganization into People’s Communes.

Simultaneously, Mao championed a nationwide push towards rapid industrialization, with a particular focus on steel production. The nation was mobilized to build backyard steel furnaces, which often resulted in the destruction of useful farm tools and household utensils to provide the necessary scrap metal. The majority of the resulting steel, produced by inexperienced peasants, was of such poor quality that it was unusable.

While pursuing these policies, the culture of political fear that existed within the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) during Mao’s leadership led to a lack of transparency and accountability, and repressed any form of dissent. Officials often reported inflated production numbers to meet unrealistic targets, resulting in systemic misinformation. This aggravated problems as it led to higher grain procurement by the CCP, believing that they had a surplus, which was then exported or left to rot in poorly constructed granaries.

Unfortunately, these policies’ implementation was largely based on unrealistic targets and a lack of understanding of economic principles and agricultural science. In agriculture, the creation of People’s Communes disrupted traditional farming practices without introducing scientifically sound alternatives. Techniques such as close planting and deep plowing, touted by the government as revolutionary, were actually detrimental. The obsession with steel production led to masses of untrained people producing substandard steel, which was useless for industrial applications. Moreover, the diversion of labor from agriculture to steel production exacerbated food shortages. Ironically, the drive to create steel often resulted in the destruction of useful agricultural tools.

The economic effects of these policies were devastating. According to data from the World Bank, China’s GDP contracted by 27 percent from 1959 to 1961. Industrial output declined due to the production of low-quality steel, and the misuse of labor and resources resulted in long-term damage to China’s economic infrastructure. The focus on steel production also drew labor away from farming, intensifying the food crisis. Despite the intended goal of the Great Leap Forward, it instead led to an economic regression from which it took many years for China to recover.

The human cost was even more tragic. As a result of the Great Leap Forward’s policies, China was plunged into what is now known as the Great Chinese Famine. According to Dali Yang, a political science professor at the University of Chicago, grain output decreased by approximately 15 percent from 1958 to 1961, a catastrophic drop when considering China’s huge population. Scholars estimate that the death toll from the famine ranged from 15 million to 45 million. Frank Dikötter, in his book “Mao’s Great Famine,” claims the higher figure, positing that at least 45 million people died unnatural deaths between 1958 and 1962. In 1960, at the peak of the famine, the death rate was a staggering 25.4 per thousand, compared to 10.8 per thousand in 1957, according to data provided by the Chinese government.

The suffering endured by the Chinese people during this period was immense. Families were ripped apart, and social order was thrown into chaos. Instances of cannibalism were reported. Dikötter recounts grim tales of a father forced to bury his child alive or of families selling their children in exchange for food. There were also reports of brutal punishments meted out by local officials to those who failed to meet grain quotas or were caught hoarding food. This atmosphere of fear, desperation, and societal breakdown left psychological scars that would be felt long after the famine ended.

Cultural Revolution

The Cultural Revolution, officially known as the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, was initiated by Mao in 1966. Galvanized in large part by Mao’s concerns over the corruption of Marxist-Leninist ideology in the Soviet Union, the Cultural Revolution’s stated goal was to preserve “true” communist ideology by purging remnants of capitalist and traditional elements from Chinese society. However, the campaign spiraled into a period of chaos and violence, resulting in immense suffering and loss for the Chinese people.

The political repression that began with the Cultural Revolution was brutal and severe. Mao called for “bombarding the headquarters,” a metaphorical call to rebel against perceived bourgeois elements within the party. The Red Guards—a group primarily comprised of zealous students—became the revolutionary force, ready to uphold Mao’s ideology at any cost.

One of the most vivid illustrations of the violence endured by the Chinese people during the Cultural Revolution was the widespread public shaming and persecution known as “struggle sessions.” These were essentially public humiliations of perceived class enemies, who were paraded through streets, verbally and physically abused, and tortured. Victims were forced to confess their “crimes” against the revolution, and these sessions often resulted in executions. According to the historian Song Yongyi, at least 1.5 million people died in these struggle sessions and mass killings, and millions more were displaced or severely traumatized.

The violence during the Cultural Revolution afflicted all of Chinese society. For instance, a vice-principal of a school in Beijing, Bian Zhongyun, was beaten to death by her students. She is widely considered to be one of the first victims of the Red Guards’ violence. In another horrifying incident in Guangxi province, reports of cannibalism surfaced where victims’ organs were consumed in public rallies.

One of the most impactful aspects of the Cultural Revolution was the effect on the education system. Schools across China were closed, disrupting the education of an estimated 110 million students and essentially creating a “lost generation.” This generation was sent to the countryside for “re-education through labor,” where they performed hard manual labor and lived in conditions of severe hardship. Without formal education or skills, they were caught in a cycle of poverty and disenfranchisement that lasted long after the Cultural Revolution ended.

Family life, too, was deeply impacted. Children were encouraged to denounce their parents if they showed signs of “bourgeois thinking.” Zhang Hongbing, a fervent Red Guard, reported his mother for criticizing Mao. His mother was subsequently tried and executed, a decision that Zhang deeply regretted later in life. The erosion of family trust and traditional familial structures caused deep societal scars that took decades to heal.

The economic impact of the Cultural Revolution was catastrophic. Industrial production fell by 13.7 percent between 1966 and 1968, and per capita grain output dropped by nearly 14 percent from 1966 to 1971. This decline in agricultural production led to widespread food shortages, malnutrition, and in some cases, starvation. The chaos and violence in urban areas led to a mass exodus of people to the countryside, causing further strain on rural resources.

Another horrific by-product of the revolution was the destruction of cultural heritage. Temples, shrines, books, art, and artifacts were destroyed in a frenzy to wipe out the “Four Olds”–old ideas, old culture, old customs, and old habits. Intellectuals, artists, and cultural figures were especially targeted, resulting in a profound loss for Chinese arts, literature, and culture. According to one estimate, up to 4,922 of 6,843 officially designated sites of scenic and historical interest were damaged or destroyed during the Cultural Revolution.

Even high-ranking party members were not spared. Chinese President Liu Shaoqi was ousted and died under harsh conditions in prison, while Deng Xiaoping, the General Secretary of the Communist Party, was publicly humiliated and sent to work in a tractor factory. His son, Deng Pufang, was thrown out of a window by Red Guards, leaving him paralyzed for life.

Overall, Mao is estimated to have been responsible for the deaths of more than 60 million of his own people as a direct result of his socialist policies.

Post-Mao China

When Mao—who had become increasingly ill during the last decade of his tenure—finally died in 1976, a massive power vacuum opened up within the CCP. After a brief period of instability in which many of Mao’s sycophants were either imprisoned or removed from power, the more free market-oriented Deng Xiaoping took the reins. Deng, along with his successors Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao, transitioned China into a period of state-managed capitalism—which shared more in common with fascism than it did socialism.

However, the ascendance of Xi Jinping as the paramount leader of China in 2012 has seen China return more heavily to its communist roots. Xi’s reign has introduced a number of socialist initiatives designed to strengthen central control and reinstate the influence of the CCP, bringing the nation closer to its Maoist origins.

Xi’s policies represent a spectrum of state control: from the emphasis on Marxist ideologies in education, a clampdown on private businesses, and even to the integration of technology with social governance, such as the controversial social credit system. These shifts reflect Xi’s vision of a new era for socialism with Chinese characteristics, intending to guide China towards becoming the world’s strongest superpower.

The education sector under Xi has seen an increased emphasis on Marxism and socialist ideology. In 2018, the Chinese government launched a nationwide initiative to deepen the study of Marxist theory in schools and universities, in an attempt to imbue the younger generation with communist values. Xi himself has advocated for “patriotic education,” using it as a tool to foster national loyalty and adherence to CCP orthodoxy.

In the business sector, private companies have faced increased scrutiny and regulation. This scrutiny has especially targeted the technology sector, with high-profile investigations and fines for anti-competitive practices. Xi’s administration has also pressed private companies to align more closely with Communist Party policies, advocating for a greater CCP presence within corporations and strengthening “state capital” in the mixed economy.

The Belt and Road Initiative is another aspect of Xi’s vision for socialism. It aims to extend China’s influence globally, aligning with Xi’s aspiration to turn China into a “global leader in terms of comprehensive national power and international influence” by mid-century. The initiative also integrates with his domestic policy, promoting industrial capacity cooperation and creating alternative markets for China’s products.

However, one of the most prominent and contentious of Xi’s policies has been the establishment and implementation of the social credit system. Envisioned as a comprehensive system to monitor and shape the behavior of individuals, corporations, and government entities, the system uses a range of data to assign a “social credit score.”

In essence, the social credit system seeks to cultivate a “trustworthy” society. It operates by rewarding “good” behavior and punishing “bad” behavior with individuals’ scores affecting their access to a range of services. These rewards and punishments can manifest in various forms: from faster internet services and better job prospects to travel restrictions and exclusion from certain schools.

The system collects data from multiple sources, such as financial information, criminal records, social media activity, and even shopping habits. It has received criticism for its potential for invasion of privacy, and for the risks it poses concerning data security. Critics argue that it reflects an Orwellian vision of society, where the state exerts total control over its citizens.

While the Chinese government contends that the system promotes trust and social stability, it is viewed by many as a powerful tool of social control, reinforcing the Chinese Communist Party’s dominance. After all, it is the CCP that determines what constitutes “good” and “bad” behavior.

Although these policies have faced resistance both domestically and internationally, they continue to shape China’s path, reflecting Xi’s determination to assert the Communist Party’s supremacy. While Xi’s vision of a “new era” for socialism with Chinese characteristics is still unfolding, it’s clear that it involves increased state control and a move back towards communist ideology.

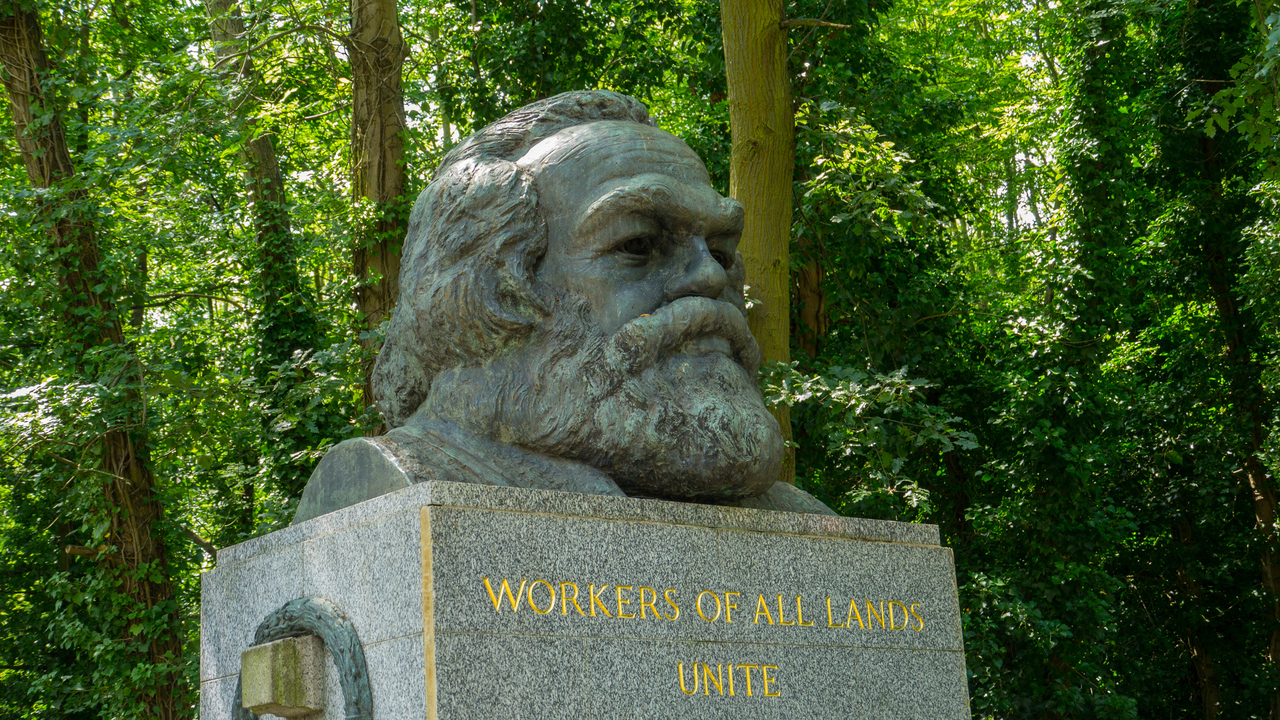

Photo by TUBS, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported

Jack McPherrin ([email protected]) is a managing editor of StoppingSocialism.com, research editor for The Heartland Institute, and a research fellow for Heartland's Socialism Research Center. He holds an MA in International Affairs from Loyola University-Chicago, and a dual BA in Economics and History from Boston College.