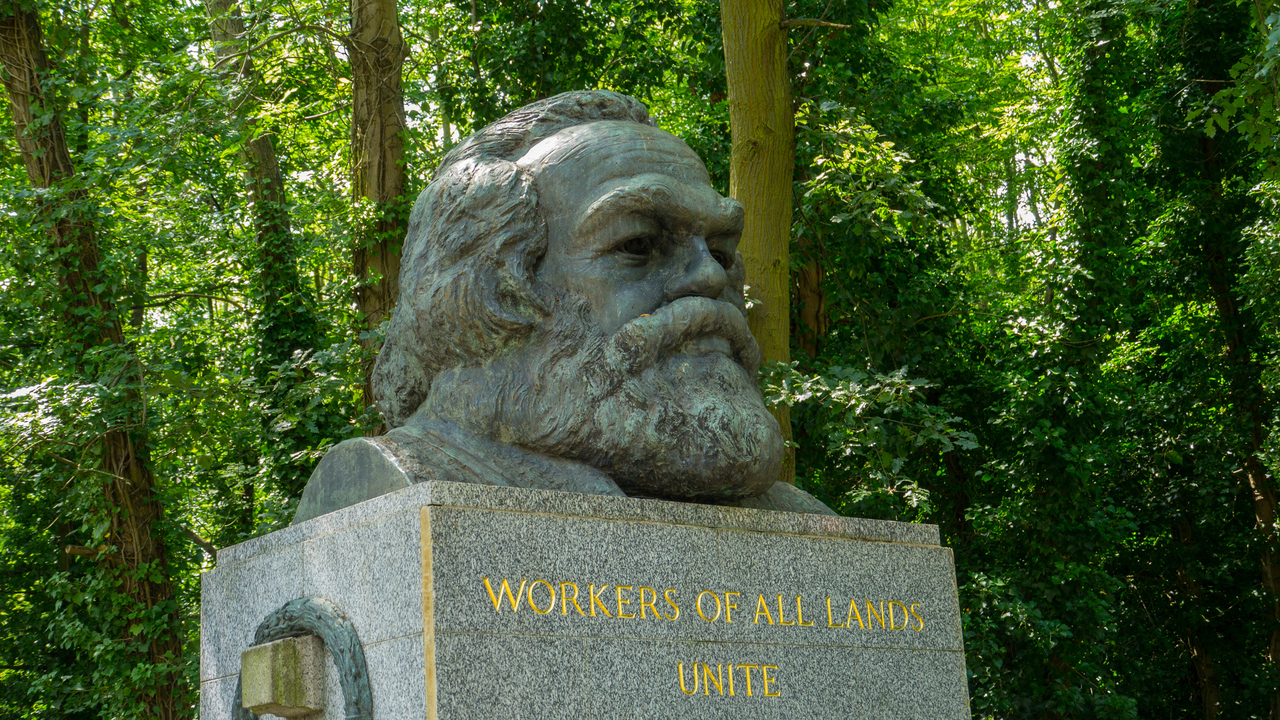

In essence, The Communist Manifesto has become the contemporary guidebook for socialism because it has been used throughout the 20th and 21st centuries to justify bloody socialist revolutions and the formation of socialist regimes.

The Communist Manifesto begins with: “The history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles,” which essentially theorizes that all of human history can be boiled down into one simple theme: class warfare.

According to Marx and Engels, the vast majority of societal conflicts stem from “class struggles” between wealthy property owners (the “bourgeoisie”) and workers (the “proletariat”). Further, they believed that “the bourgeoisie forged the weapons that bring death to itself; it has also called into existence the men who are to wield those weapons — the modern working class — the proletarians.”

This dynamic between the so-called oppressors and oppressed forms the foundation for Marx and Engels’ thesis. They believe that the working class would eventually unite and overthrow the owners of the means of production, who they contended hoard wealth and power while taking advantage of the poor working class.

As Marx and Engels wrote, “The immediate aim of the Communists is the same as that of all other proletarian parties: formation of the proletariat into a class, overthrow of the bourgeois supremacy, conquest of political power by the proletariat.”

Once the overthrow had taken place, which Marx and Engels were supremely confident would occur throughout the world, they envisioned a new society built on the following 10 pillars:

- Abolition of property in land and application of all rents of land to public purposes.

2. A heavy progressive or graduated income tax.

3. Abolition of all rights of inheritance.

4. Confiscation of the property of all emigrants and rebels.

5. Centralisation of credit in the hands of the state, by means of a national bank with State capital and an exclusive monopoly.

6. Centralisation of the means of communication and transport in the hands of the State.

7. Extension of factories and instruments of production owned by the State; the bringing into cultivation of waste-lands, and the improvement of the soil generally in accordance with a common plan.

8. Equal liability of all to work. Establishment of industrial armies, especially for agriculture.

9. Combination of agriculture with manufacturing industries; gradual abolition of all the distinction between town and country by a more equable distribution of the populace over the country.

10. Free education for all children in public schools.

Then, Marx and Engels argue, “When, in the course of development, class distinctions have disappeared, and all production has been concentrated in the hands of a vast association of the whole nation, the public power will lose its political character. Political power, properly so called, is merely the organised power of one class for oppressing another. If the proletariat during its contest with the bourgeoisie is compelled, by the force of circumstances, to organise itself as a class, if, by means of a revolution, it makes itself the ruling class, and, as such, sweeps away by force the old conditions of production, then it will, along with these conditions, have swept away the conditions for the existence of class antagonisms and of classes generally, and will thereby have abolished its own supremacy as a class.”

In other words, according to Marx and Engels, once the proletariat takes power from the bourgeoisie and implements the communist 10-point plan, class warfare will disappear, equality will triumph, government will no longer be necessary, and everyone will live in harmony.

Marx and Engels also argued that a worldwide communist revolution was inevitable because they believed that workers would always be taken advantage of by management. Yet, in the years and decades after The Communist Manifesto was published, the exact opposite occurred, especially in the United States. By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, labor unions were formed, collective bargaining was recognized, the eight-hour workday and five-day work week was normalized, and workers’ wages steadily rose. These reforms, along with a steadily rising standard of living and formation of a consumer-driven middle class, show how misguided Marx and Engels were in their vision of the future. Despite the growing evidence that the plight of the working class was steadily improving, socialists, particularly in Europe, still adhered to Marxist orthodoxy and rallied to create a series of socialist states that they believed would bend the arc of history in favor of collectivism.

However, as the record shows, this socialist paradise has never come to fruition, despite Marx and Engels’ blueprint being applied numerous times, under several different forms, in many unique places.

Chris Talgo ([email protected]) is the editorial director and a research fellow at The Heartland Institute, as well as a researcher and contributing editor at StoppingSocialism.com.