Contrary to claims by Marxist and socialist historians, the National Socialists of Germany were far more hardcore socialist and Marxist-leaning than most people realize. In reality, Hitler was heavily influenced by Marxism. He did not just march under a parade of red flags or wear communist armbands during the Bavarian Soviet Republic of 1919. No, he actually ran for a low-level position, “Deputy Battalion Representative,” a few days after the communists seized control of Bavaria. Hitler worked briefly for the Communist Party of Germany until more than 30,000 Weimar Republic and Freikorps troops laid siege to Munich and killed hundreds of Bavarian Red Army troops in street battles. After the battle, Hitler and everybody in his army barracks was arrested, interned, and interrogated. He escaped with his life by becoming an informer.

Former Nazi leader Hermann Rauschning documented this Marxist influence on Hitler. He revealed a conversation wherein Hitler told him: “In my youth, and even in the first years of my Munich period after the war, I never shunned the company of Marxists of any shade.” In all likelihood, this is where Hitler got his idea to incite his own revolutionary movement and attack the Munich authorities during his 1923 Beer Hall Putsch, which resulted in 20 deaths.

In truth, the National Socialists’ proclivity towards hardcore revolutionary socialism was substantial. In a 1925 New York Times article, Joseph Goebbels, the future Reich Minister of Propaganda and later briefly Chancellor of Nazi Germany, revealed his Marxist overtones. In that NYT wire story, Dr. Goebbels is identified as the man who declared to a beer-hall crowd that, “Lenin was the greatest man, second only to Hitler, and that the difference between communism and the Hitler faith was very slight.” In fact, Hitler and the Nazis acknowledge their gratitude to the Russian communists’ semantic customs. After Hitler’s appointment to the German chancellorship, the Nazi party required all members to address each other as Genossen, or “Comrades,” according to Richard Pipes, the Harvard University historian who fled Poland after the Nazi invasion.

Goebbels was “happy to describe himself as a ‘German Communist’” during his college days. In a 1925 diatribe against capitalism, he wrote, “It would be better for us to go down with Bolshevism than live in eternal slavery under capitalism.” In a 1925 diary excerpt, he wrote, “We will turn National Socialism into a party of class struggle,” a major tenet of Marxism. He talked about the Nazi Party as being a “party of revolutionary socialists” in 1929. In 1943, he spoke about the prospects of a socialist Germany winning the war, declaring, “If Germany stays united and marches to the rhythm of its revolutionary socialist outlook, it will be unbeatable.”

Due to the appeal of authoritarian socialism, many National Socialists were drawn to Marxist-Leninist ideology that promoted anti-capitalism, social equality, welfarism, classlessness, social justice, and “revolutionary nationalism.” Hitler was so impressed with Russian communists that he tried to appropriate the Soviet Union’s iconic hammer and sickle imagery and reapply it to Nazism. In the Führer’s May Day Speech at the Tempelhof Air Field, Berlin on May 1, 1934, he boasted, “The hammer will once more become the symbol of the German worker and the sickle the sign of the German peasant.”

Although political competitors, especially when it came to the labor movement, Hitler and Nazi leaders often joined forces together with Communists. In 1932, Hitler allied with the Communist Party of Germany against the Social Democrats in support of a workers’ wage dispute. Hitler’s “brownshirts” and red flag-waving Communists marched side-by-side through the streets of Berlin and destroyed any busses whose drivers had failed to participate in the workers’ strike. Alongside the communists, Nazis ripped up tramlines, stood together and “shouted in unison” and “rattled their collecting tins” to get donations for their strike funds in support of the Revolutionary Trade Union Opposition (RGO) for the communists and National Socialist Factory Cell Organization (NSBO) for the Nazis. According to English historian Ian Kershaw, many middle-class Germans suspect that “Hitler was arm in arm with Marxism,” and “thought Hitler far on the Left.”

Communist Reichstag deputies championed the Nazis’ anti-capitalist agenda before Hitler rose to become chancellor. For instance, a 1931 bill was introduced in the Reichstag to impose a ceiling of 4 percent on interest rates, expropriate the holdings of “the bank and stock exchange magnates” and of all “Eastern Jews” without any compensation, and nationalize all the big banks. Fearful that the bill’s Bolshevist approach would harm the Nazi Party’s image, Hitler ordered it to be withdrawn. The Communist Party of Germany stepped forward, took the Nazi Party’s exact verbiage, and reintroduced it, word for word. In many cases, the communists and Nazis were legislative buddies, often voting together under Stalin’s motto “First Brown, Then Red.”

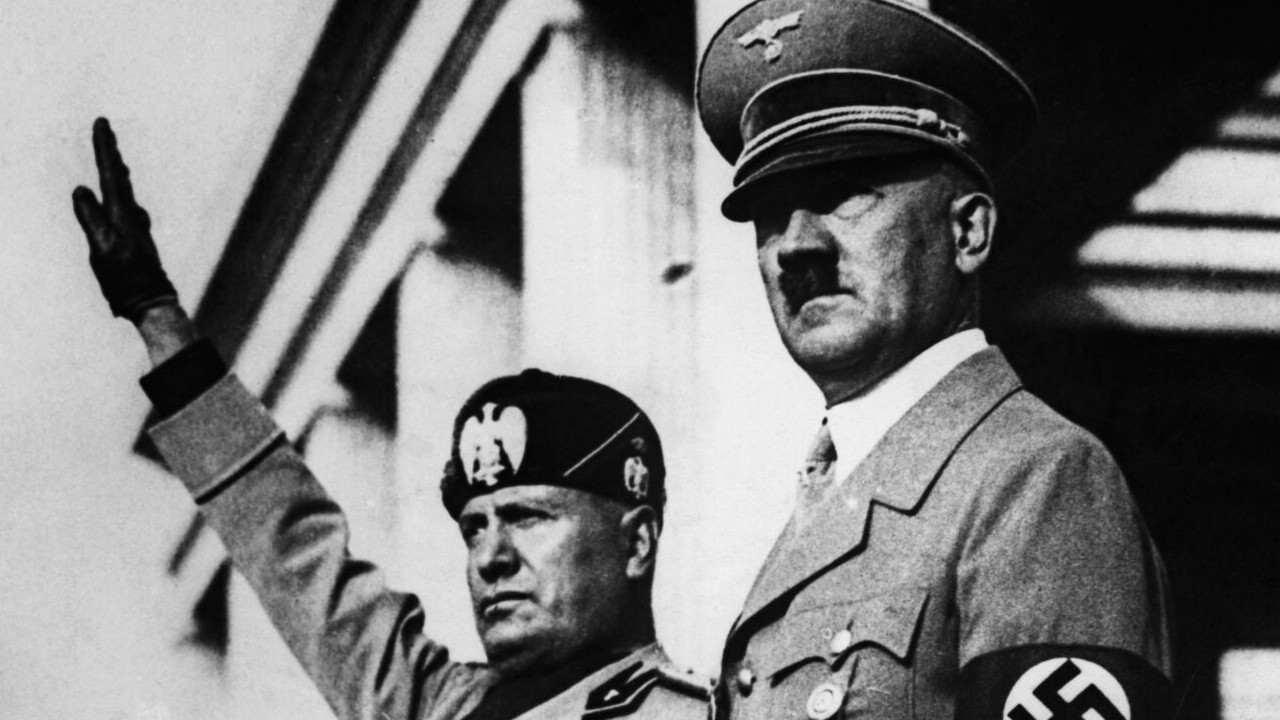

Even many Social Democrats were captivated by Hitler’s and Mussolini’s charms as the vanguard of a socialist new world order. Some leaders in the socialist left-wing Fabian Society, such as George Bernard Shaw, found Hitler to be “a very remarkable, very able man.” Acting like a fanboy of Hitler, Shaw wrote in 1935, “The Nazi movement is in many respects one which has my warmest sympathy.” Moreover, Shaw insisted that Mussolini had preceded Hitler in being a National Socialist, praising the Italian dictator in 1927 as a leader who was “farther to the Left in his political opinions than any of his socialist rivals.”

And yet, Shaw also displayed undying praise for Stalin and the Soviet Union. During his 10-day visit to the Soviet Union in 1931, Shaw eagerly displayed his admiration for the “great Communist experiment.” Trying to impress his hosts, Shaw was “concerned precisely with establishing himself as the grand old man of socialism who had always been a defender of the Bolshevistic Revolution and who had known and corresponded with Lenin.” George Orwell noted this affection that Shaw held for Nazism and communism, concluding that “Bernard Shaw… declared Communism and Fascism to be much the same thing, and was in favour of both of them.” Such a response might classify Shaw’s admiration for fascism and communism as a “Fascist-Marxist devotee.”

George Orwell acknowledged these socialist and doctrinal similarities between the two totalitarian nations. In his 1941 essay “The Lion and the Unicorn,” Orwell treated the Nazis as part of the socialist clan, writing that “Internally, Germany has a good deal in common with a socialist state,” and that the factory owner only owns his property in name, and had essentially been “reduced to the status of a manager. Everyone is in effect a State employee.”

There is other evidence that German Communists and National Socialists were very compatible. During the late 1920s and early 1930s, a trend developed where Nazi and Communist recruits regularly switched their party affiliation since Nazi and Communist ideology and tactics appeared so similar. This practice became a well-known joke by the 1930s when the Nazis were said to be “Nazi brown outside and Moscow red inside,” and were known as “Beefsteaks” or “Beefsteak Nazis.”

In his 1936 book Hitler: A Biography, the German historian and journalist Konrad Heiden wrote that “there were large numbers of Communist and Social Democrats among” Röhm Sturmabteilung (SA) ranks, often “called beefsteaks.” In fact, so many communists and Social Democrats populated Nazis stormtrooper ranks that a common joke went: “one SA man says to another: ‘In our storm troop there are three Nazis, but we shall soon have spewed them out.’” This acknowledged the fact that underneath the Nazi’s brown shirt lurked a red-blooded communist.

Other political parties in Germany also identified the same Nazi-communist parallels. In the late 1920s, Chancellor Hermann Müller of the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) employed the beefsteak analogy when he remarked, “red equals brown,” meaning that Communists and Nazis posed an equal danger to liberal democracy.

With such close ideological similarities, the Nazis had a policy of encouraging German communists to join them, regarding them as excellent recruits. Many Marxists were lured to egalitarian socialism, social equality, classlessness, social justice, anti-capitalism, nationalization, and the revolutionary nationalism of the Nazis. This explains why historians concede that Röhm’s SA had a Marxist outlook that appealed to so many Nazis leaders.

One stat shows the extent of the Communist-Nazi close affinity in Germany. Rudolf Diels, head of the Gestapo from 1933 to 1934, remarked in 1933 that in the city of Berlin, around “70 percent” of fresh SA recruits were former communists. According to political scientist Peter H. Merkl, both the SA and SS were saturated with socialists and Marxists, writing: “The utopians and those who speak of a Marxist republic have the highest membership in the SA and SS (77.6 and 63 percent respectively).”

By 1932, the German public began to worry about the National Socialists’ propensity to march in lockstep with Communists. According to Polish-American academic Richard Pipes in Russia Under the Bolshevik Regime, both Joseph Goebbels and Otto Strasser were seen as “National Bolsheviks,” or the Nazi left, who wanted closer ties with Stalin’s Russia. They planned to bolster the Soviet Union’s economy so that the Communists and National Socialists could take down Britain and France. They also favored worker strikes and the nationalization of most banks and industries. Considered the undisputed right-hand man by Nazi party officials, Gregor Strasser sought a nationalist form of social revolution, a sort of national identity infused with “real socialism.” Such socialist and revolutionary rhetoric should not be surprising. In Hitler’s Beneficiaries: Plunder, Racial War, and the Nazi Welfare State, Götz Aly exposed that most Nazi party leaders borrowed heavily from the “intellectual tradition of the socialist left” and “many of the men who would become the movement’s leaders had been involved in communist and socialist circles.”

In 1940, Winston Churchill also clearly stated that Nazism and Sovietism were cut from the same cloth, remarking that “Nazi despotism is an equally hateful though the more efficient form of the communist despotism.” Later in 1948, he further reflected in his first volume The Second World War series that: “Fascism was the shadow or ugly child of communism… As Fascism sprang from Communism, so Nazism developed from Fascism.”

Other political leaders expressed Churchill’s views about the similarities between communism and Nazism. Kurt Schumacher, the first chairman of the revised Social Democratic Party of Germany in 1946, caused a media stir when he derided communists as “red-painted Nazis,” accusing the two political movements of enabling each other. In fact, Schumacher argued that the Soviet Union had pursued not internationalist goals, but instead “nationalist and imperialist” ones that paralleled Nazism.

Hitler’s true Marxist-lite colors continued to stain Germany red. By the time of the fall 1932 election, many Germans had had enough of Hitler’s revolutionary bombast. The German National People’s Party (DNVP) and German conservatives began to see Hitler as a radical socialist and denounced Nazism as “bolshevism in nationalist wrapping.” The main bone of contention was that Hitler’s party had come out in favor of a strike by Berlin transport workers in November of 1932.

There were many other incidents of collaboration between the National Socialists and communists before Hitler’s chancellorship, including short-term accords and friendship between leaders of the Nazi Party and the German Communist Party. For instance, in 1931, the communist Prussian party welcomed the Nazis with open arms, touting them as “working people’s comrades” who were assisting them in pulling down their common enemy, the Social Democratic Party of Germany. The Nazis and the communist Prussian party organized a united front to overthrow the Socialist Democratic government of Prussia, as ordered by Stalin’s Comintern. This Nazi-communist plebiscite became known as the “Red Referendum.”

The KPD repeatedly courted Nazi followers. In early November 1931, the German communists came out with praise for “National Socialist workers” and “proletarian supporters of the Nazi Party,” referring to them as “honest fighters against the system of hunger.”

So, what did the other German political parties think of the National Socialists before they took power? The two Liberal parties of Germany—the German People’s Party (DVP) and the German State Party (DSP)—warned their members that the National Socialists represented “a party of the radical left.” One DVP publication denounced the socialist elements of the Nazis, warning: “Whether national or international, it is still socialism … of the most radical type.”

To the DVP and DSP way of thinking, the Nazis “would make a more compatible ally of Communism,” than would liberal or conservative parties. In fact, the DVP often linked National Socialism with Marxism. They warned their members that the National Socialists were anti-capitalists, who proposed the abolishment of “interest capital.” Such socialist policies would be disastrous, mirroring the collapsed Soviet economy of 1921. The DVP told their constituents that Hitler’s “socialistic programs are not one penny better than other Socialists.” These national liberal parties accused the Nazi deputies in the Reichstag of backing, “the most incredible Communist-sponsored proposals. But, of course, they don’t tell the middle class and the peasants about this. In front of them they portray themselves as ‘anti-Marxists’… beware of wolves in sheep’s clothing.”

Of course, the Nazi-Communist reaction against the German Liberal parties was mutual. According to Graham Hallett in The Social Economy of West Germany, “the Communists and National Socialists hated the liberals more than they hated each other.”

Conservative and non-socialist nationalistic parties in Germany were also hostile to the Nazis. Alfred Hugenberg (1865–1951), the main leader of the conservative German National People’s Party (DNVP), finally had enough with his short-lived coalition with Hitler’s NSDAP. He concluded that the Nazis were the “main enemy” of Germany. By the fall of 1932, conservative leaders stated that they saw no difference between the “red Bolshevism” of the communist KPD and the “brown Bolshevism” of Hitler’s Nazi Party. The Nazis retaliated by branding the conservatives as being reactionary and bourgeois.

Even The New York Times acknowledged the close similarities between Nazism and communism after their non-aggression pact was signed in 1939, editorializing that the issue remained clear: “Hitlerism is brown communism, Stalinism is red fascism.” They also affirmed, “The world will now understand that the only real ‘ideological’ issue is one between democracy, liberty and peace on the one hand and despotism, terror and war on the other.”

The Wall Street Journal also joined the ranks of those who compared Nazis and Stalinists as evil twins, observing: “The American people know that the principal difference between Mr. Hitler and Mr. Stalin is the size of their respective mustaches.” Some socialist leaders echoed the same sentiment about Stalin’s fascist communism, including Norman Thomas, who wrote, “Such is the logic of ‘totalitarianism’ that ‘communism,’ whatever it was originally, is today Red fascism.” In fact, in a February 24, 1941, speech, as reported by The Bulletin of International News, Hitler declared, “basically National Socialism, and Marxism are the same.” One of the biggest similarities between Nazi and communist tactics is a diehard reliance on state authority to socially re-engineer society by emasculating the individual means of self-determination and consent.

Other well-respected historians have made the same claim. French historian François Furet, a former communist intellectual, wrote that “It was in Nazi Germany that Bolshevism was perfected; there, political power truly absorbed all spheres of existence, from the economy to religion, from technology to the soul.”

What about the journalists and authors who lived in Europe during the Nazi-Soviet era? The British journalist, Frederick Augustus Voigt, was one of the most vocal. In 1938 he wrote, “Marxism has led to Fascism and National Socialism, because, in all essentials, it is Fascism and National Socialism.” He asserted, “National Socialism would have been inconceivable without Marxism.”

And, then there was Dorothy Thompson, an American journalist and radio broadcaster who interviewed Hitler. Later in 1934, she was expelled from Nazi Germany. She wrote in 1938, “Fascism, Nazism, and Communism are all Collectivism. In this respect, they are all alike.” In 1939, she revealed a bit more, stating, “And now the beginning of the expropriation of church lands in Austria, have all revealed the true face of National Socialism, which more and more among pious Germans is called, under their breaths, ‘the brown Bolshevism.”

Peter Drucker, an Austrian-American professor and management educator who lived in Germany until 1933, made one of the most astute observations about Nazism in his 1939 The End of Economic Man. He argued, “Fascism is the stage reached after communism has proved an illusion.”

Walter Lippmann, the twice-winning Pulitzer Prize journalist, also weighed in on the close parallels between fascist and communist ideologies. In The Good Society of 1937, Lippman asserted, “The totalitarian states, whether of the fascist or the communist persuasion, are more than superficially alike as dictatorships… They are profoundly alike.”

Vera Micheles Dean, a Russian American political scientist who fled Russia, observed in her 1939 book Europe in Retreat, “What the Nazis have introduced in Germany is a form of graduated Bolshevism, directing their first assault upon Jewish capitalists—bankers, industrialists and businessmen—but posed to train their guns on the Catholic Church and Aryan capitalists.”

To the British Fabian playwright George Bernard Shaw, Communism and Fascism held a special space in his heart. An eager fan of Hitler, Mussolini, and Stalin, Shaw declared in 1934, “As a red-hot Communist I am in favor of fascism,” and that “The Nazi movement is in many respects one which has my warm sympathy.”

What did communist leaders of the era think about their movement? One such member was Margarete Buber-Neumann, a leader of the Communist Party of Germany. In May 1935, the Comintern ordered her back to Moscow to serve as a translator only to be arrested in 1937 and imprisoned in several Soviet Gulag labor camps. In 1940, the Soviets sent her to a Nazi concentration camp. In her Under Two Dictators: Prisoner of Stalin and Hitler book, she attested, “The Soviet practice under Stalin betrayed the original idea and established in the Soviet Union a kind of Fascism.”

Another German communist, Otto Rühle, equated Nazism with Bolshevism. Angry over the 1939 Hitler-Stalin Pact, he condemned the Soviet Union in “The Struggle against Fascism Begins with the Struggle against Bolshevism.” Rühle argued that “Russia was the example for fascism… Whether party ‘communists’ like it or not … the state order and rule in Russia are indistinguishable from those in [Fascist] Italy and [Nazi] Germany.”

So, was German National Socialism a hardcore socialist and Marxist-leaning dictatorship? The answer should be obvious. I have presented just a few examples from my book Killing History on the dysfunctional political spectrum. There should be little doubt over the closeness of Hitler’s National Socialism to Stalin’s nationalistic Bolshevism. As Goebbels glowingly defined the political anatomy of the Third Reich, the German National Socialists were indeed establishing a “socialist people’s state” to rival Stalin’s Soviet state.

PHOTO: Adolf Hitler. Photo by Museoviraston Kuvakokoelmat. Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0).

Stopping Socialism is a project of The Heartland Institute and The Henry Dearborn Center for Human Rights, a nonprofit association of professionals and scholars.