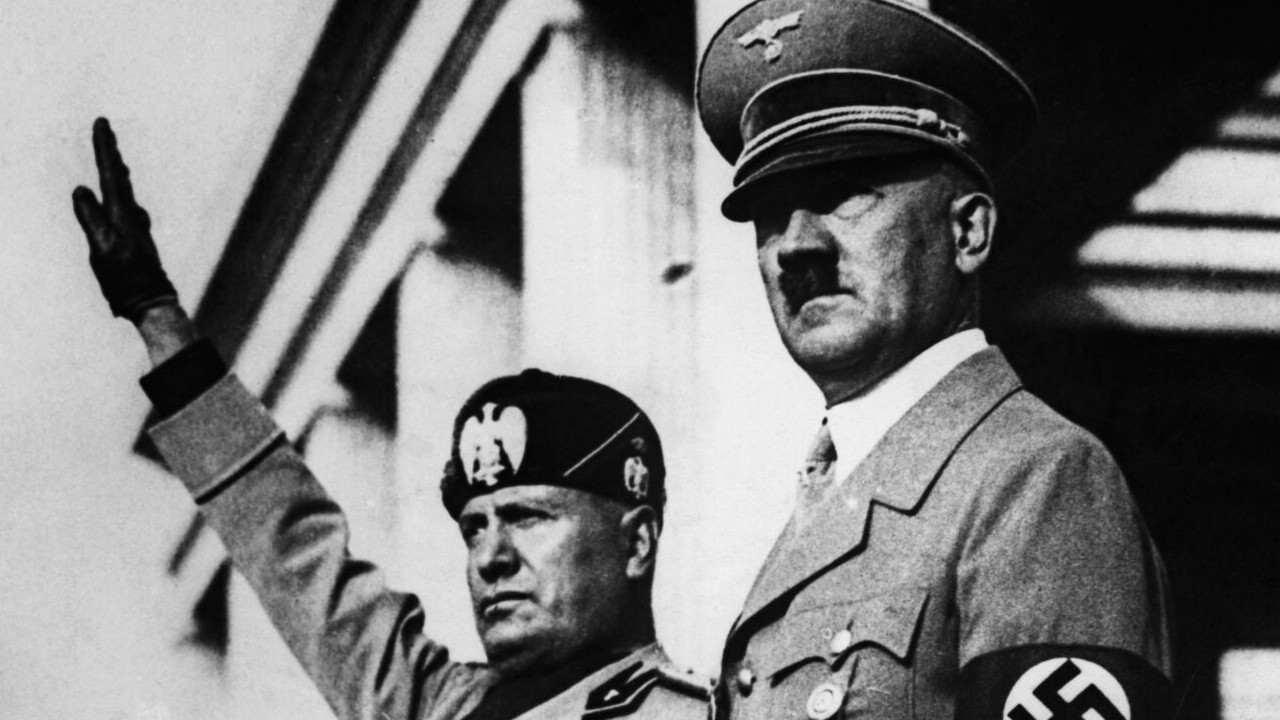

Both Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini were perhaps the original and most dedicated ideological warriors for social justice. But the German National Socialists and Italian Fascists represented more than a brutal force that sent stormtroopers and blackshirt thugs to shout down rivals, block free speech, break shop windows, throw tear gas at opponents, and bash heads. They also represented a nationalist, collectivist, and Marxist-inspired ideology that sought a “socially just” welfare society by redistributing everyone’s wealth.

The Nazis threatened and bullied almost everyone, any outspoken opponent or opposition political party, including conservative-nationalist parties. During the 1932 fall elections in Germany, the Nazis were almost at war with the conservative German National People’s Party (DNVP), where according to the German historian Hermann Beck, “the Nazis broke up German National election meetings with stink bombs and tear gas” and heckled a DNVP deputy and called him “Jew boy.” The German national press retaliated with charges of Nazism awash in socialism and violence, and stern warnings of economic doom if the Nazis were to gain power. The DNVP and German conservatives denounced Nazism as “bolshevism in nationalist wrapping.”

According to German historian Götz Aly, what made German National Socialism different from earlier versions of socialism was its “drive to couple social equality with national homogeneity, a concept that was popular not only in Germany.” From the very start, Hitler made it plain that social justice was an important ingredient for a healthy state. In his 1920 speech, “Why We Are Anti-Semites,” Hitler proclaimed to thousands of Nazi followers in Munich: “we do not believe that there could ever exist a state with lasting inner health if it is not built on internal social justice.” Throughout his regime, Hitler promoted his “Völkisch equality” goals for society. In one speech to factory workers in 1940, Hitler promised “the creation of a socially just state, a model society that would continue to eradicate all social barriers.”

This advocacy for social justice was combined with their contempt for Jewish capitalism. A Nazi propaganda poster from 1933 read: “Because Adolf Hitler’s Third Reich wants social justice, big Jewish capitalism is the worst enemy of this Reich and its Führer.” To the National Socialists, every German of pure blood was entitled to equality before the law and equality of opportunity, not as individuals, but as part of the collectivity of a “people’s community” (Volksgemeinschaft).

In essence, Nazi Germany had become a redistributive regime that sought to rob the rich to pay the poor to fashion a universal social utopia—a sort of social justice mecca that has been dubbed a “racist-totalitarian welfare state.” In fact, National Socialist “policies were remarkably friendly toward the German lower classes, soaking the wealthy and redistributing the burdens of wartime to the benefit of the underprivileged.” Götz Aly described how Hitler’s regime financed their lavish social safety net for proper racial pedigree Germans, writing that to “achieve a truly socialist division of personal assets, Hitler implemented a variety of interventionist economic policies, including price and rent controls, exorbitant corporate taxes, frequent ‘polemics against landlords,’ subsidies to German farmers as protection ‘against the vagaries of weather and the world market,’ and harsh taxes on capital gains, which Hitler himself had denounced as ‘effortless income.’”

To achieve socialism and social justice, the Nazis had to engage in extensive social welfare programs. According to Michael Burleigh in The Third Reich: A New History, “charity” was “integral to National Socialism.” He explained that their social welfare policies were an “uncomplicated reflection of human altruism” that “became a favoured means of mobilizing communal sentiment… underrated, but quintessential, characteristic of Nazi Germany.”

Joseph Goebbels applauded the generosity of Hitler’s welfare state, boasting in a 1944 editorial titled “Our Socialism,” that “We and we alone [the Nazis] have the best social welfare measures. Everything is done for the nation… the Jews are the incarnation of capitalism.” It was also Goebbels who defined the two opposing forces during World War II. In his “England’s Guilt” speech in late 1939, Goebbels declared that “England is a capitalist democracy. Germany is a socialist people’s state.” Proclaiming that “English capitalists want to destroy Hitlerism,” Goebbels argued that the capitalists in England are the “richest men on earth. The broad masses, however, see little of this wealth.”

To the National Socialists, wealth inequality was a horrendous injustice that had to be solved by the state. Both German National Socialists and Italian Fascists worked feverishly to strengthen and enlarge their social safety nets. In addition to old-age insurance (social security) and universal socialized health care, the Nazi administration provided a plethora of social safety net goodies: rent supplements, holiday homes for mothers, extra food for larger families, more than 8,000 day-nurseries, unemployment and disability benefits, old-age homes, interest-free loans for married couples, to name just a few. But there was more. Under the Third Reich’s redistributive policies, the main social welfare organization—the “National Socialist People’s Welfare” (NSV)—was not only in charge of doling out social relief but “intended to realize the vision of society by means of social engineering.” In other words, the Nazi’s welfare system ushered in a menagerie of welfare programs: aid to poor families and pregnant women, nutrition, welfare for children, ad nauseam, but also put energy into “cleansing of their cities of ‘asocials,’” which ushered in a no-welfare-benefits for-the-unfit program, based on a welfarism that was committed to a sort of social Darwinist collectivism. Other asocials and underperforming workers were housed in Gestapo-operated “labor education camps,” a new category that by 1940 encompassed two hundred camps that held 40,000 inmates.

Established in May of 1933, the NSV deemed that they had created the “greatest social institution in the world.” And to keep it that way, Hitler ordered its new chairman, Erich Hilgenfeldt, to “see to the disbanding of all private welfare institutions,” which began the Nazi’s effort to both nationalize charity and control society by determining who received social benefits. And yet, the banning of privately operated welfare organizations implied far more. Such social engineering policies meant that the Nazis were entrenched in their statist left-wing beliefs that government had to be the sole provider of welfare services. By socializing welfare in Germany, the national socialists exhibited their true red-revolutionary colors, following in the socialist footsteps of the Soviet Union. Even today, most American left-wing progressives would be reluctant to deny Non-Government Organizations (NGO) the opportunity to do charity work for the community. So, does this place American Progressives on the far right because the Nazi’s social welfare programs were so extremely left-wing?

The Nazi welfare state was so massive and all-encompassing that a German businessman’s letter published in Günter Reimann’s 1939 book, The Vampire Economy, declared that “these Nazi radicals think of nothing except ‘distributing the wealth.’” The same businessman also revealed that “Some businessmen have even started studying Marxist theories, so that they will have a better understanding of the present economic system” and that the German business community “fear National Socialism as much as they did Communism in 1932.”

Mussolini also displayed similar social justice causes. In his early years as a Marxist, labor union leader, and disciple of French Marxist Georges Sorel, Mussolini supported violence in the streets to bring about a proletarian state through labor strikes. When he started to embrace nationally-based socialism, his blackshirts roughed up and force-fed castor oil to opponents. Nonetheless, his advocacy of nationalistic socialism did not preclude him from supporting social justice issues, welfarism, public works projects, and a socialist totalitarian state. One of the components of Italian Fascism was interventionistic economics, especially during the 1930s. Mussolini supported central planning, heavy state subsidies, protectionism (high tariffs), steep levels of nationalization (three-fourths of the economy), rampant cronyism, large deficits, high government spending, steep taxes, bank and industry bailouts, overlapping bureaucracy, massive social welfare programs, crushing national debt, and bouts of inflation.

As UC Berkeley political scientist A. James Gregor asserted, Italy spent considerable funds on elaborate social welfare programs that were “motivated by the ‘moral’ concern with abstract ‘social justice.’” He wrote: “Fascist social welfare legislation compared favorably with the more advanced European nations and in some respect was more progressive.”

During the early 1930s, Mussolini spoke about equality and social justice and his admiration for the labor movement, declaring in a speech to workers in Milan: “Fascism establishes the real equality of individuals before the nation… the object of the regime in the economic field is to ensure higher social justice for the whole of the Italian people.”

Under the new Italian Social Republic, Mussolini’s administration enacted a “socialization law” in 1944 that called for more nationalization of industry, where “workers were to participate in factory and business management,” along with collectivized land reform. One section of the socialization law proclaimed: “Enforcement of Mussolinian conception on subjects such as much higher Social Justice, a more equitable distribution of wealth and the participation of labor in the state life.” According to Australian historian R.J.B. Bosworth, the Italian Social Republic “obsessively emphasized” commitments to socialization and a “variety of fascist equalitarianism and an amplified fascist welfare state.”

On another occasion, Mussolini declared in one of his last interviews (March 20, 1945): “We are fighting to impose a higher social justice. The others are fighting to maintain the privileges of caste and class. We are proletarian nations that rise up against the plutocrats.”

Not only did Hitler and Mussolini engage in violence by teargassing, beating up, and shouting down opponents like the modern-day Antifa, but they also committed atrocities against humanity in their effort to defend social justice, making them the quintessential social justice warriors of the 20th century. Now, if only the violent black-shirted activists in the Antifa movement today would realize that they are merely a resurrection of yesterday’s goose-stepping fascists.

PHOTO: Benito Mussolini and Adolf Hitler, Munich, 1937. Photo by Tullio Saba. Public Domain Mark 1.0.

Stopping Socialism is a project of The Heartland Institute and The Henry Dearborn Center for Human Rights, a nonprofit association of professionals and scholars.