Obviously, no mother-son relationship is complete without its requisite ups and downs. However, Karl Marx’s strained relationship with his doting mother, especially when he sought the family inheritance, provides a glimpse into the dark heart of one of history’s most misunderstood men.

Although history books treat Marx and his loyal followers with kid gloves, the real story of the man behind the Communist Manifesto would shock and appall even the most ardent of his followers.

In a previous edition of this series, which is dedicated to revealing the real Karl Marx—as opposed to the whitewashed version of the man that appears in textbooks—we explored his abhorrent racism. In this piece, we discover how he viewed his own family, especially his mother in her dying days, as nothing more than an obstacle to his inheritance of the family fortune.

For context, Karl Marx’s father died in 1838, leaving a substantial sum of money to his wife, Henrietta—Karl’s mother. According to Marx biographer Nathaniel Weyl, “By the time the estate was settled in 1841, Henrietta Marx had already advanced her son 1,111 talers on his inheritance, this apparently being over and above substantial gifts of cash from ‘your mother who loves you.’” Yet, this was not good enough.

A bitter family feud erupted, with Karl demanding increasingly more money, even as his sisters and mother pleaded with him to provide for himself. After all, Karl was 23 years old! At this point, Marx’s five sisters began to view him quite negatively. His closest and favorite sister, Sophie, even told him “that it was undignified and irresponsible of him to count on living the life of a perpetual parasite.” Unfortunately, Sophie’s sage advice fell upon deaf ears.

Shortly thereafter, things went from bad to worse. Enraged, Marx wrote to his friend Arnold Ruge, “My family … in spite of their wealth, put obstacles in my way which place me, for the moment, in the most straightened circumstances.” He even went on to accuse his own mother of “skullduggery” because she refused to give him more money after his father died.

Looks like Karl Marx was obsessed with wealth redistribution even when it came to redistributing his own father’s wealth to himself. For Marx, the ends always justified the means!

As the years went on and Marx’s mother refused to hand her son more money, his anger and resentment grew. In 1854, Marx wrote to Engels, “I can do nothing with my old woman, who still keeps herself in Trier, unless I sit on her neck.”

In 1861, Marx’s frustrations with his mother withholding his inheritance boiled over. He sent a scathing letter to Engels, which read, “I got a reply from my old lady yesterday. Nothing but ‘affectionate’ talk, but no cash. She also told me, what I have known for a long time, that she is 75 years old and feels many of the infirmities of age.”

In late 1863, Marx’s mom passed away. Here is an excerpt of Karl’s letter to Engels, after he heard the news of his mother’s death, “Two hours ago, a telegram came that my mother is dead. Destiny demanded one of us from this house. I myself already stood with one foot in the grave. Under present conditions, I am more needed than the old woman.” There was no mention of grief or despair.

Marx also told Engels he must “go to Trier at once to settle the inheritance.” He then asked Engels to give him money for the trip.

Shortly thereafter, Marx traveled to Trier. Once there, he settled the affairs of his inheritance. Although Marx received a substantial sum of money (850 pounds, about 15 times the annual salary of a skilled worker), he squandered it in a short period.

Although one cannot glean a full picture of a man based upon his relationship with his family, it sure seems that Karl Marx viewed his own flesh and blood (including his loving mother) as nothing more than sheer objects (or pawns) in his quest for grandeur.

That alone ought to make one question whether Marx’s political philosophy of wealth distribution and class envy is built upon anything more than Marx’s own demented view of how he could coast through life at the expense of others, including his own family.

Maybe Marx’s ill-conceived social-political philosophies are as intellectually lacking as Marx’s morals, which were practically non-existent throughout his life. Morally, spiritually, and materially, Marx was always bankrupt.

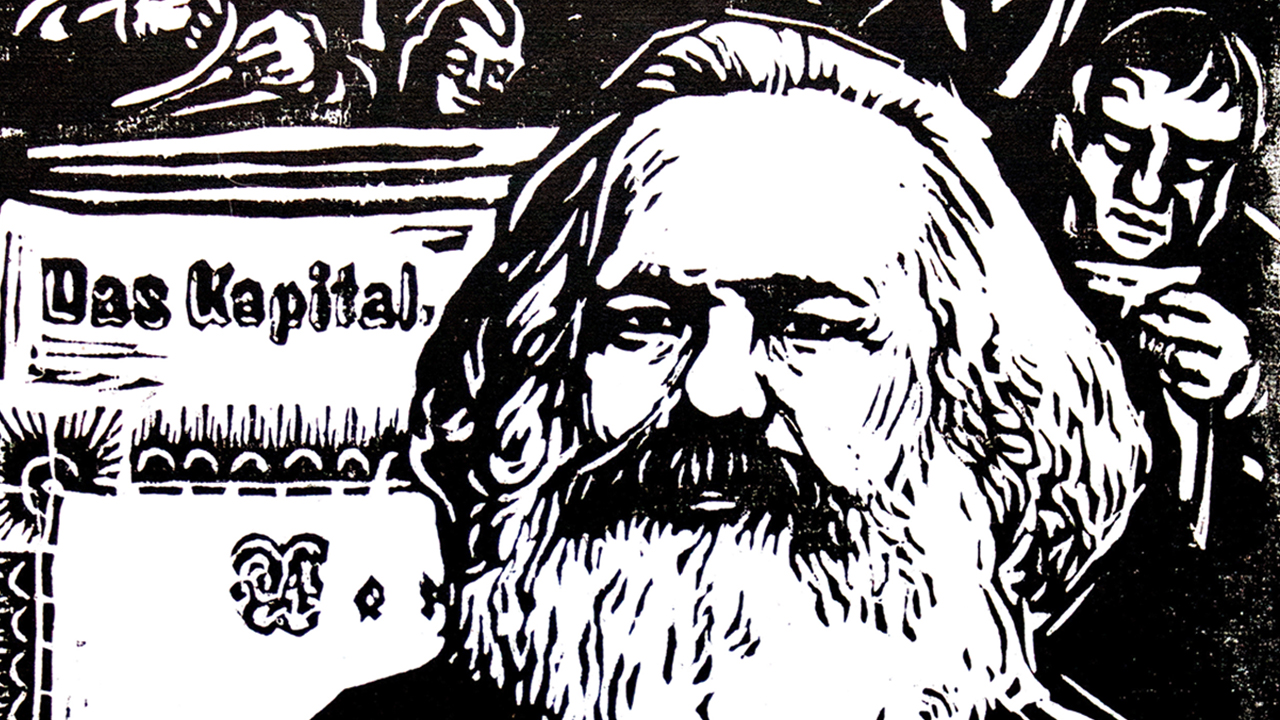

PHOTO: Karl Marx by Robert Diedrichs, 1970. Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Germany (CC BY-SA 3.0 DE)

Chris Talgo (CTalgo@heartland.org) is the editorial director and a research fellow at The Heartland Institute, as well as a researcher and contributing editor at StoppingSocialism.com.