Almost every day, some pundit or commentator paints conservatives and even libertarians with the toxic brush of Hitlerism. These uninformed critics repeatedly accuse the Fuhrer of right-wing extremism. But according to many scholars, that narrative has been found to be completely false. A number of historians, including the German Thomas Weber, are now declaring that Hitler was personally involved with a whole different crowd who opposed anything remotely conservative or classical liberal.

In truth, Hitler was involved in an extreme left-wing political movement and revolution, sporting a red armband while working on behalf of the Communist Party of Germany in Munich. In fact, on the second day after the Communists declared the Bavarian Soviet Republic on April 6, 1919, Hitler sought and won an elected position in the Communist government. Bluntly, Hitler participated in a Communist regime even during a period that resembled a Lenin-like reign of terror.

Where is the historical proof? It comes from military archives from Hitler’s barracks, which Thomas Weber discovered in Munich during research for his 2011 book Hitler’s First War. Thought to be lost during WWII Allied bombing campaign of Munich, these archives provide clear evidence that Hitler threw his hat into the ring within two days of the communist seizure of the Bavarian government. Elected “Deputy Battalion Representative,” Hitler appeared determined to support the revolutionary socialist Räterepublik, which was led by the Jewish, Russian-born Communist revolutionary leader Eugen Leviné. And in doing so, Hitler was pledging his allegiance to Lenin’s Soviet Russia. In fact, Weber revealed that Hitler earned the second-highest number of votes in his unit, resulting in his victory for the Ersatz-Bataillons-Rat position. According to Weber, Hitler’s actions made him a “more significant cog in the machine of Socialism,” helping to “sustain the Soviet Republic.”

Hitler’s duties included liaising with the new soviet republic leaders and their Department of Propaganda. In other words, Hitler joined the Marxist insurgents, took to the streets, and assisted in promoting the policies of the Communist Party of Germany. The Communists quickly seized homes, cash, and food supplies. When food shortages became critical, especially milk, the Communist response was: “What does it matter? . . . Most of it goes to the children of the bourgeoisie anyway. We are not interested in keeping them alive. No harm if they die—they’d only grow into enemies of the proletariat.” As the situation worsened, the Communists raised a Red Army, estimated to be 20,000 soldiers, shot hostages, and planned to abolish money, following in lockstep with the repressive measures of the Russian Bolsheviks.

Other evidence of Hitler’s involvement includes a still photograph of a red-armband-wearing Hitler taken by Heinrich Hoffmann, who eventually became Hitler’s court photographer. In later years both Hoffmann and his son confirmed that Hitler was indeed in the photo. Of course, as Weber wrote, “all Munich-based military units and thus Hitler’s regiment, too, were part of the Red Army” and had to wear red armbands. In that sense, “Hitler served in the Red Army,” although most Munich regiments did not actively support the communist regime.

Despite his subsequent reputation for anti-Marxist tirades, Hitler did not fight or oppose the Communists. He was serving them, although he expressed few details about this horrific episode in his life. One thing seemed certain; he did not try to escape from the Lenin-backed political thicket in Munich, nor did he join the anti-Bolshevik armed forces of General Franz Ritter von Epp. Thomas Weber makes it clear in his 2017 book Becoming Hitler that the future leader of the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (Nazis) “remained in his post for the entire lifespan of the Soviet Republic,” and “did not join a Freikorps with his comrades prior to the defeat of the Soviet Republic.” Because he had failed to join the anti-communist forces to overthrow the Räterepublik red government, Hitler later suffered “scornful reproaches from Ernst Röhm,” co-founder of the Nazi’s Sturmabteilung (Stormtroopers). Otto Strasser, an early member of the Nazi Party, also criticized Hitler for failing to join the armed forces of General von Epp to “fight the Bolsheviks in Bavaria,” asking: “Where was Hitler that day?”

In the end, the Communist republic was quickly overthrown in fierce street battles with over 600 casualties. But there is more to this story. During the street battles, Hitler was arrested and interned with other captured communist adherents of the Bavarian Soviet Republic. In his 1936 book Hitler: A Biography, Konrad Heiden, a Munich-born journalist and a Social Democrat himself, remarked that during this period, Hitler engaged in heated discussions where he “espoused the cause of Social Democracy against that of the Communists.” That seemed reasonable, since Hitler and everyone in his barracks were in serious trouble. They were all interrogated over whether they were a Communist or a Communist sympathizer. The punishment for being a Communist was execution, imprisonment, or exile. So, was Hitler protecting himself and hiding his true loyalty to Communism, or did he, in fact, pledge his loyalty to the Social Democrats, a more moderate movement that had its original roots in orthodox Marxism?

We may never know the true extent of Hitler’s intentions or state of mind during this period. It does appear he was briefly a Communist sympathizer until it became too dangerous and then decided to support what he later called “national Social Democracy.” Nonetheless, Hitler did tell one of his confidants in later years that “In my youth, and even in the first years of my Munich period after the war, I never shunned the company of Marxists of any shade.”

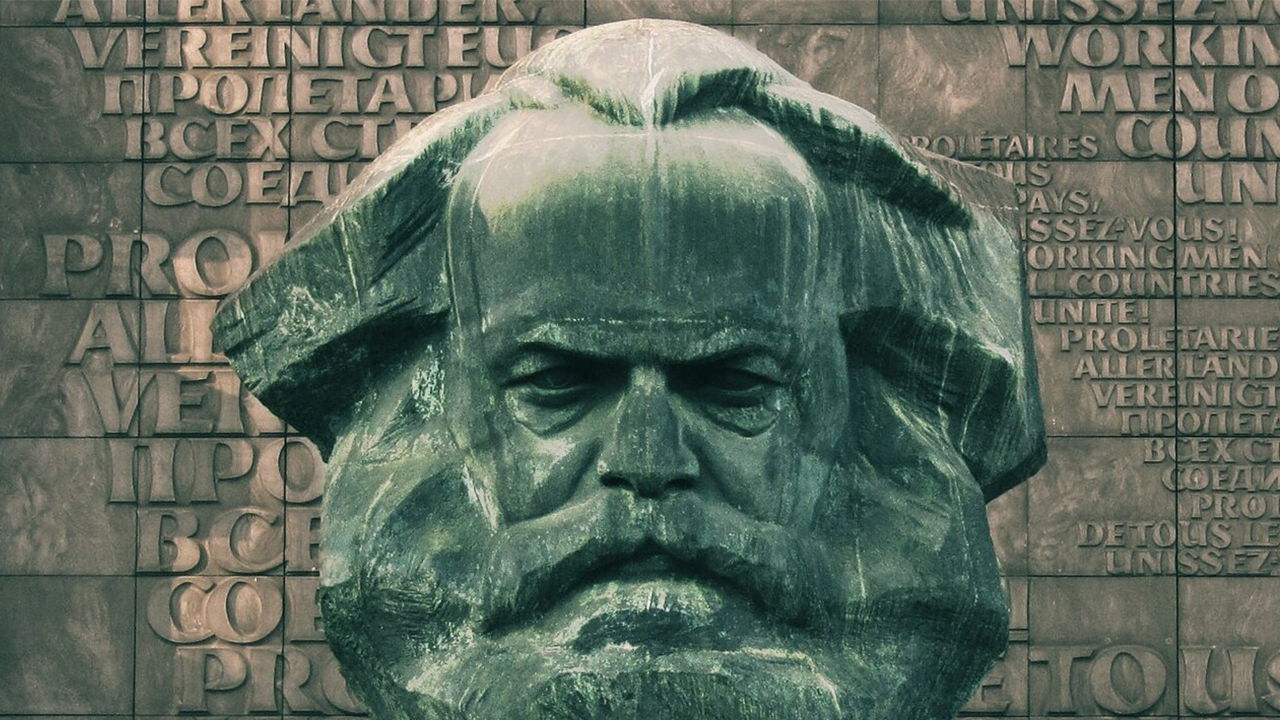

PHOTO: Portrait of Hitler. Photo by Marc Beech. Public Domain Mark 1.0.