While President Joe Biden’s administration doesn’t seem to need an excuse to spend money, two recurring arguments for his gigantic $2.3 trillion infrastructure proposal are that our roads and bridges are “crumbling” and that modernization would generate economic growth and jobs — hence its name, the American Jobs Plan. But none of this clever marketing makes any of these claims true.

Let me start by pointing out that, to the extent that people think about roads and bridges when they hear the word “infrastructure,” they should know that only $621 billion of the $2.3 trillion is for transportation — and of that sum, only $115 billion is for repairing roads and bridges. The rest of the bill is mostly a handout to private companies that already invest heavily in infrastructure. These subsidies will come with federal red tape and regulation and hinder job creation, not bolster it.

Also, while our infrastructure could certainly be modernized and could use some maintenance, it’s not crumbling. According to the World Economic Forum, U.S. infrastructure is ranked No. 13 in the world — which, out of 141 countries, isn’t too shabby, especially when considering the enormous size of our country and the challenges that presents.

Yet as Washington Post columnist Charles Lane notes, it would be more accurate to bundle European nations together, since they share a significant amount of infrastructure, which would move the United States into fifth place.

Moreover, while the American Society of Civil Engineers’ 2021 report card gave the United States a C-, this is its best grade in two decades — meaning that the quality of roads, bridges, inland waterways or ports has been improving each year, without a congressional rescue plan. This fact doesn’t quite fit the crumbling-infrastructure narrative that politicians and the media like to tout.

Academics also refute the idea that infrastructure is crumbling. Reviewing a large body of research in a National Bureau of Economic Research paper, Wharton University economist Gilles Duranton and his co-authors state:

“Perhaps our main conclusion is that, on average, U.S. transportation infrastructure does not seem to be in the dire state that politicians and pundits describe. We find that the quality of interstate highways has improved, the quality of bridges is stable, and the age of buses and subway cars is also about constant.”

This is an important reminder that the private sector doesn’t seem to have any problem maintaining its infrastructure assets, as we see in the difference with railroads. Passenger rail is in mostly bad shape when owned publicly, whereas privately owned freight rail is mostly strong in quality. The best way to improve infrastructure isn’t to throw taxpayers’ money at it, but to privatize things such as passenger rail, airports and air traffic controllers, as many other countries have done already.

Also, while the idea that building infrastructure will bring about more economic growth makes for a good talking point, it doesn’t work in practice. It’s proven that when there’s already economic growth occurring in a specific area, infrastructure spending targeted to support the boom will promote even more growth. But simply building infrastructure in the hope that it will create growth isn’t supported by evidence. For instance, in their review of the literature, Duranton and his colleagues find “little compelling evidence about transportation infrastructure creating economic growth.” One reason is that a supply of more infrastructure is likely to be a total waste of money if there’s no actual demand for it.

What’s more, looking at spending on highway construction in the Great Recession stimulus bill, economist Valerie A. Ramey concluded that “there is scant empirical evidence that infrastructure investment, or public investment in general, has a short-run stimulus effect. There are more papers that find negative effects on employment than positive effects on employment.” What that spending does do, however, is displace private investments. This is unfortunate, since the Congressional Budget Office found that private spending produces twice the return as does public spending.

Finally, in theory, government spending could lead to higher growth in the longer term. Unfortunately, legislators’ well-documented tendency to make decisions based on politics often leads them to favor projects that are outdated, expensive and never profitable at the expense of private and profitable alternatives. Rail and transit projects come to mind.

The bottom line is this: Politicians make a lot of promises, but we shouldn’t always believe them.

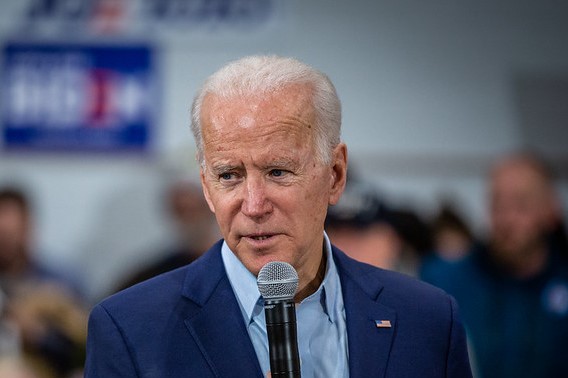

PHOTO: Joe Biden at McKinley Elementary School. Photo by Phil Roeder. Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0).

Veronique de Rugy is the George Gibbs Chair in Political Economy and senior research fellow at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University. Her primary research interests include the U.S. economy, the federal budget, cronyism, taxation, tax competition and financial privacy. Her popular weekly columns address economic issues ranging from lessons on creating sustainable economic growth to the implications of government tax and fiscal policies. She has testified numerous times in front of Congress on the effects of fiscal stimulus, debt, deficits and regulation on the economy.

De Rugy blogs about economics at National Review's The Corner. Her charts, articles and commentary have been featured in a wide range of media outlets, including the "Reality Check" segment on Bloomberg Television's "Street Smart," The New York Times' Room for Debate, The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal, CNN International, "Stossel," "20/20," C-SPAN's "Washington Journal" and Fox News Channel. She was also named to the Politico 50, the influential media outlet’s “guide to the thinkers, doers and visionaries transforming American politics” in 2015.

Previously, de Rugy has been a resident fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, a policy analyst at the Cato Institute and a research fellow at the Atlas Economic Research Foundation. Before moving to the United States, she oversaw academic programs in France for the Institute for Humane Studies Europe.

She received her master's degree in economics from Paris Dauphine University and her doctorate in economics from Pantheon-Sorbonne University.

Read De Rugy's workhere.