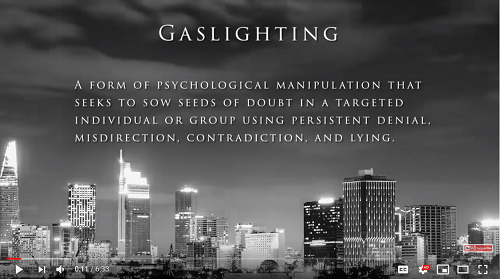

A seemingly effective way for politicians to justify our need for their services is to fabricate or exaggerate a problem, promise to fix said problem with a new program or lots of spending and then claim victory in the form of public acclaim and reelection.

A good example of this behavior is President Joe Biden’s Build Back Better plan, which reflects a tweet by then-candidate Biden that he does “not buy for one second that the vitality of American manufacturing is a thing of the past.”

His plan asks for $400 billion to purchase American-made equipment, along with $300 billion in government spending on research and development. Hundreds of billions of dollars’ worth of additional subsidies will be used to encourage the production and sale of other domestically manufactured products.

Yet this money won’t be spread thinly and equitably across all sectors. It will be focused on preferential, politically sexy and privileged sectors such as electric vehicles and wind turbines.

If this sounds like a good old industrial policy, that’s because it is. This idea isn’t new; it has been on every left-wing politician’s platform for decades. What is actually a bit unique is that support for industrial policy is also coming from many conservatives this time around. They may not care so much about building green cars, but they share in the goal of reviving American manufacturing by constraining globalization and subsidizing favored industries.

Here’s the rub: American manufacturing is generally healthy, especially prior to the trade wars and the pandemic. A data- and chart-rich new paper by the Cato Institute’s Scott Lincicome about a “Manufactured Crisis: ‘Deindustrialization,’ Free Markets, and National Security” documents American manufacturing’s excellent health. It disproves the alleged justification for industrial policy and debunks all the national security arguments trotted out to justify protectionism. And Lincicome’s analysis and data also apply nicely to Biden’s case for industrial policy.

The claim that we need a national industrial policy because U.S. manufacturing is in decline is usually based on two trends: the fall in both U.S. manufacturing employment and the sector’s declining share of total U.S. economic output (measured by gross domestic product). Each of these trends, however, started decades ago. And neither tells you anything about the productive capacity of the nation overall or the vitality of the industries being targeted by the industrial policy.

As Lincicome shows, the reduction in manufacturing employment is occurring in every industrialized nation, including those countries with economies more centered on manufacturing than the United States. It’s also occurring in nations with longstanding trade surpluses in goods, and even in those countries that already have aggressive industrial policies. The real reason for a decline in manufacturing employment is mostly due to labor-saving technologies that raise worker productivity. In fact, anyone who wants to understand this reality ought to visit contemporary steel mills. They look nothing like mills of the past, as they’re automated, clean and employ highly skilled and well-paid workers.

The decrease in the share of GDP generated by manufacturing is mostly the result of the fact that our modern economies are increasingly service economies. That’s consumers’ choice. This trend, too, exists in all developed countries. Lincicome also demonstrates that when compared to other countries’ sectors (and contrary to pro-industrial policy advocates), U.S. manufacturing continues to be at or near the top of most categories, including output, exports and investment. Industrial capacity is also growing, and industry-specific data show strengths where it counts (durable, high-value-added goods).

I can only scratch the surface of all the data presented in Lincicome’s excellent paper. The bottom line is this: If you’re anxious about U.S. manufacturing and wondering whether its health or perceived decline justifies industrial policy, you must read Lincicome’s work. Even the U.S. semiconductor industry, which is often used as an excuse for subsidies and protectionism, “is profitable and expanding — in many ways still globally dominant — and is investing billions of its own dollars to stay that way,” as Lincicome explains. The same is true for pharmaceutical and nonpharmaceutical medical goods, along with many other industries commonly targeted for support.

Winston Churchill once said, “Never let a good crisis go to waste,” to emphasize that a crisis gives leaders an opportunity to do the things they couldn’t get away with doing before. As it turns out, manufactured crises can do the same for eager legislators.

PHOTO: President Joe Biden. Photo by Matt Johnson. Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0).

Veronique de Rugy is the George Gibbs Chair in Political Economy and senior research fellow at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University. Her primary research interests include the U.S. economy, the federal budget, cronyism, taxation, tax competition and financial privacy. Her popular weekly columns address economic issues ranging from lessons on creating sustainable economic growth to the implications of government tax and fiscal policies. She has testified numerous times in front of Congress on the effects of fiscal stimulus, debt, deficits and regulation on the economy.

De Rugy blogs about economics at National Review's The Corner. Her charts, articles and commentary have been featured in a wide range of media outlets, including the "Reality Check" segment on Bloomberg Television's "Street Smart," The New York Times' Room for Debate, The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal, CNN International, "Stossel," "20/20," C-SPAN's "Washington Journal" and Fox News Channel. She was also named to the Politico 50, the influential media outlet’s “guide to the thinkers, doers and visionaries transforming American politics” in 2015.

Previously, de Rugy has been a resident fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, a policy analyst at the Cato Institute and a research fellow at the Atlas Economic Research Foundation. Before moving to the United States, she oversaw academic programs in France for the Institute for Humane Studies Europe.

She received her master's degree in economics from Paris Dauphine University and her doctorate in economics from Pantheon-Sorbonne University.

Read De Rugy's workhere.